I (famously?) hate musicals, so this entry on my list of favorite films may come as a surprise. Chicago occupies the top spot on the short list of musicals I do like (including Cabaret, Jesus Christ Superstar, and, only recently, The Sound of Music among those that have been made into films), and it’s not just because it is an outstanding example of the genre, it’s an amazing motion picture, too.

To recap: Roxie Hart (Renee Zellweger) wants nothing more to be a cabaret performer, but her dead-end marriage to blue collar Amos (John C. Reilly) isn’t opening any doors. When her lover Fred Casely’s (Dominic West) promise to get her an audition is revealed to be just a ploy to get her into bed, Roxie shoots him in a fit of rage, landing her on Murderess’s Row with celebrity murderer Velma Kelly (Catherine Zeta-Jones), the singer whose career Roxie most idolized. In prison, the two vie for public sympathy, favors from prison warden Mama Morton (Queen Latifah), and the attention of high powered lawyer Billy Flynn (Richard Gere). The two women trade barbs as one star rises and the other falls, leaning Velma to pitch Roxie on the idea of becoming a duo. When both women are upstaged by the triple-murder committed by Kitty Baxter (Lucy Liu, in a treasured cameo), they reluctantly agree that their shared star power is the only way to find success.

Chicago, written by Kander and Ebb with additional book work by Bob Fosse, premiered on stage in 1975, placing it among several of my beloved musicals of that era. Thematically, it predicts so much about our contemporary moment, perhaps because these things have always been part of the Zeitgeist since the show premiered: obsession with celebrity, inability to differentiate notoriety from celebrity, manipulation of the legal system (to the explicit benefit of non-immigrant white people, and the influence journalism has on the body politic. Chilling, really, when you stop and think about how many of these ideas are part of daily American discourse.

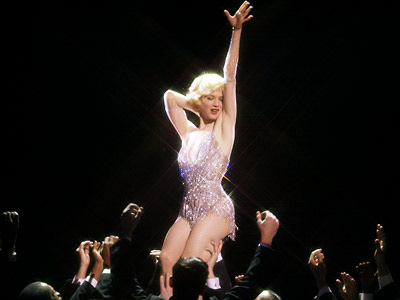

Every person in this cast turns in a stellar, unexpected, and virtuoso performance. Who could ever forget Richard Gere’s smarmy “All I Care About Is Love,” the manipulation of Roxie as a puppet in “We Both Reached for the Gun” and his sweat-drenched tap solo in the courtroom. Zellweger shines in her solos as well, especially in her eponymous number where she’s flanked by a coterie of tuxedoed men and mirrors (her two greatest loves?). And Latifah’s raucous “When You’re Good to Mama” letting her chew the scenery in the most gratifying way. But it’s Zeta-Jones in her Oscar-winning turn that anchors this film.

Zeta-Jones’s Velma is dismissive, selfish, unrepentant, and arrogant. But from the first moment she rises onto the cabaret stage to belt “All That Jazz,” she cannot be ignored. Sexuality drips from every note, every sweep of her arms and legs. No one is having more fun in this film than she is during “Cell Block Tango,” when she explains how she “blacked out” after murdering her sister and husband, caught in bed together. But it’s the sheer athleticism of “I Can’t Do It Alone,” Velma’s pitch to Roxie for a team up, that centers her character. I remember at the time thinking the casting of these two women in the lead roles might have been a mistake, but really this entire cast earned their stripes, and everyone’s mettle was evident from their first minutes on screen. But it’s Velma I go back to in my mind, even now, 20 years later, when I think about the most memorable Oscar-winning performances. She really did that.

Along with the cast, the sets are a star of the show. Rob Marshall’s framing of the musical numbers as figments of Roxie’s imagination created a two-tier narrative: one, Roxie’s lived experience from stepping into the jazz club to her struggle to find work after her acquittal; and the other, her song-laden fantasies that delightfully revel in the subtext of what we see in the first narrative. We get sets and costumes with drab, washed out colors in one, and dramatic gel lighting and sequins in the other. “Cell Block Tango” remains one of the most memorable numbers in the show, with the “seven merry murderesses of the Cook County Penitentiary” flanked by stacks of cell doors backlit in red to reveal the writing silhouettes of dozens of women experiencing incarceration.

“We Both Reached for the Gun” went viral on TikTok recently as a dance challenge, with folks recreating the frenetic choreography of the journalist pool a Billy slowly convinces them of Roxie’s innocence, their chorus of “Oh yes, oh yes” and “They both reached for the gun,” repeating Billy’s mimicked words back to him, demonstrating their full indoctrination into the scheme. While this is one of my favorite dance sequences in the film, I am equally obsessed with Zellweger’s turn as the ventriloquist dummy voiced by Billy Flynn in this number. She sits on his knee serving Tyra Banks’s fantasy of broke down doll while Billy moves her limbs and literally puts words in her mouth.

Unlike most of my favorite films, I think I’ve only seen Chicago a handful of times over the past two decades. Maybe 5? While it’s a film I love to revisit—I will immediately stop my social scrolling when a clip pops up in my phone—it’s not a film I need to revisit. It’s all so perfectly documented in my memory, and treasured there as one of the best contemporary examples of what the medium of film can accomplish. There’s really nothing else like it. What a gift it was to believe alive for this moment.

![Chicago – [FILMGRAB] Chicago – [FILMGRAB]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!3IWX!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb6dabda5-1cf5-4415-8baa-2921af456244_1280x692.jpeg)